Animation Skills Include All Of The Following, Except Which?

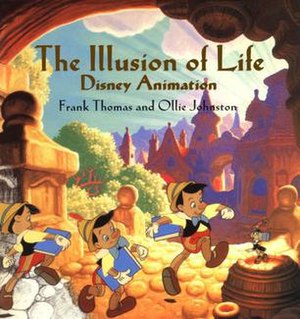

Disney'southward twelve basic principles of animation were introduced by the Disney animators Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in their 1981 book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation.[a] [one] The principles are based on the work of Disney animators from the 1930s onwards, in their quest to produce more realistic animations. The master purpose of these principles was to produce an illusion that cartoon characters adhered to the bones laws of physics, just they also dealt with more than abstract issues, such every bit emotional timing and graphic symbol entreatment.

The book has been referred to by some as the "Bible of animation",[2] and some of its principles have been adopted by traditional studios. In 1999, The Illusion of Life was voted the number one "best animation book[...] of all time" in an online poll done by Animation Earth Network.[iii] While originally intended to utilize to traditional, mitt-fatigued animation, the principles still take peachy relevance for today's more prevalent computer animation.

The 12 principles of animation [edit]

Squash and stretch [edit]

The squash and stretch principle:

rigid, non-dynamic movement of a ball is compared to a "squash" at affect and a "stretch" during the autumn and after the bounce. Also, the ball moves less in the kickoff and end (the "ho-hum in and slow out" principle).

The purpose of squash and stretch[four] is to requite a sense of weight and flexibility to fatigued or computer blithe objects. Information technology can be applied to simple objects, like a bouncing ball, or more complex constructions, like the musculature of a homo face.[5] [6] Taken to an extreme, a figure stretched or squashed to an exaggerated caste can have a comical effect.[7] In realistic animation, all the same, the about of import attribute of this principle is that an object'south volume does non modify when squashed or stretched. If the length of a brawl is stretched vertically, its width (in 3 dimensions, also its depth) needs to contract correspondingly horizontally.[eight]

Apprehension [edit]

Anticipation: a baseball game player making a pitch prepares for the activity past winding his arm back.

Anticipation is used to fix the audience for an action, and to make the action appear more realistic.[9] A dancer jumping off the flooring has to bend the knees showtime; a golfer making a swing has to swing the club back first. The technique can also be used for less physical actions, such as a character looking off-screen to anticipate someone's arrival, or attention focusing on an object that a character is about to pick up.[ten]

Staging [edit]

This principle is akin to staging, as it is known in theatre and film.[eleven] Its purpose is to direct the audition'due south attention, and make it clear what is of greatest importance in a scene;[12] Johnston and Thomas defined it as "the presentation of whatever idea then that information technology is completely and unmistakably clear", whether that idea is an action, a personality, an expression, or a mood.[11] This can be done by various means, such as the placement of a character in the frame, the apply of lite and shadow, or the angle and position of the camera.[13] The essence of this principle is keeping focus on what is relevant, and avoiding unnecessary detail.[xiv] [xv]

Directly ahead action and pose to pose [edit]

These are 2 unlike approaches to the drawing process. Straight ahead action scenes are blithe frame by frame from beginning to cease, while "pose to pose" involves starting with cartoon a key frames, and so filling in the intervals afterward.[12] "Straight ahead action" creates a more fluid, dynamic illusion of movement, and is better for producing realistic action sequences. On the other mitt, it is hard to maintain proportions and to create exact, disarming poses forth the manner. "Pose to pose" works better for dramatic or emotional scenes, where composition and relation to the surroundings are of greater importance.[16] A combination of the two techniques is oft used.[17]

In computer animation [edit]

Figurer animation removes the bug of proportion related to "straight ahead action" drawing; however, "pose to pose" is nonetheless used for reckoner animation, considering of the advantages it brings in composition.[18] The use of computers facilitates this method and can fill in the missing sequences in between poses automatically. It is notwithstanding important to oversee this process and apply the other principles.[17]

Follow through and overlapping action [edit]

Follow through and overlapping action: the galloping race equus caballus's mane and tail follow the body. Sequence of photos taken past Eadweard Muybridge.

Follow through and overlapping activity is a full general heading for ii closely related techniques which aid to return movement more than realistically, and help to give the impression that characters follow the laws of physics, including the principle of inertia. "Follow through" means that loosely tied parts of a body should continue moving later on the character has stopped and the parts should continue moving beyond the point where the graphic symbol stopped simply to be afterwards "pulled dorsum" towards the heart of mass or exhibiting diverse degrees of oscillation damping. "Overlapping activity" is the tendency for parts of the torso to motion at different rates (an arm volition move on dissimilar timing of the caput and then on). A third, related technique is "elevate", where a character starts to move and parts of them accept a few frames to catch upwardly.[12] These parts can be inanimate objects like clothing or the antenna on a car, or parts of the body, such as artillery or hair. On the homo body, the torso is the cadre, with artillery, legs, head and pilus appendices that unremarkably follow the trunk's movement. Body parts with much tissue, such as large stomachs and breasts, or the loose skin on a domestic dog, are more prone to independent move than bonier body parts.[19] Again, exaggerated utilise of the technique can produce a comical effect, while more than realistic animation must fourth dimension the actions exactly, to produce a convincing result.[20]

The "moving hold" animates between ii very similar positions; even characters sitting nevertheless, or hardly moving, tin can display some sort of movement, such as animate, or very slightly irresolute position. This prevents the drawing from becoming "dead".[21]

Slow in and slow out [edit]

The movement of objects in the real world, such every bit the human torso, animals, vehicles, etc. needs time to accelerate and tiresome downwardly. For this reason, more than pictures are drawn near the beginning and end of an activity, creating a slow in and ho-hum out effect in order to attain more realistic movements. This concept emphasizes the object'due south extreme poses. Inversely, fewer pictures are drawn within the centre of the animation to emphasize faster activity.[12] This principle applies to characters moving betwixt two farthermost poses, such as sitting down and standing upwards, but also for inanimate, moving objects, like the bouncing ball in the in a higher place analogy.[22]

Arc [edit]

Most natural action tends to follow an arched trajectory, and animation should attach to this principle by following implied "arcs" for greater realism. This technique tin be applied to a moving limb by rotating a joint, or a thrown object moving along a parabolic trajectory. The exception is mechanical movement, which typically moves in straight lines.[23]

As an object'due south speed or momentum increases, arcs tend to flatten out in moving ahead and augment in turns. In baseball, a fastball would tend to move in a straighter line than other pitches; while a figure skater moving at elevation speed would be unable to turn equally sharply as a slower skater, and would need to cover more than ground to complete the plow.

An object in movement that moves out of its natural arc for no apparent reason will appear erratic rather than fluid. For example, when animating a pointing finger, the animator should be certain that in all drawings in betwixt the 2 extreme poses, the fingertip follows a logical arc from one farthermost to the next. Traditional animators tend to draw the arc in lightly on the paper for reference, to be erased later.

Secondary activity [edit]

Adding secondary deportment to the main action gives a scene more life, and tin can assistance to support the primary action. A person walking can simultaneously swing their arms or keep them in their pockets, speak or whistle, or limited emotions through facial expressions.[24] The important matter well-nigh secondary actions is that they emphasize, rather than take attention away from the main action. If the latter is the case, those actions are better left out.[25] For case, during a dramatic motion, facial expressions volition frequently go unnoticed. In these cases, it is better to include them at the kickoff and the stop of the move, rather than during.[26]

Timing [edit]

Timing refers to the number of drawings or frames for a given activity, which translates to the speed of the activeness on film.[12] On a purely physical level, correct timing makes objects appear to obey the laws of physics. For instance, an object's weight determines how it reacts to an impetus, similar a button; equally a lightweight object will react faster than a heavy one.[27] Timing is critical for establishing a character's mood, emotion, and reaction.[12] It can also be a device to communicate aspects of a character'south personality.[28]

Exaggeration [edit]

Exaggeration is an outcome especially useful for animation, as animated motions that strive for a perfect faux of reality can look static and dull.[12] The level of exaggeration depends on whether one seeks realism or a detail style, like a caricature or the style of a specific creative person. The classical definition of exaggeration, employed past Disney, was to remain true to reality, just presenting it in a wilder, more extreme form.[29] Other forms of exaggeration tin involve the supernatural or surreal, alterations in the physical features of a character; or elements in the storyline itself.[30] It is important to employ a sure level of restraint when using exaggeration. If a scene contains several elements, there should be a residual in how those elements are exaggerated in relation to each other, to avoid disruptive or overawing the viewer.[31]

Solid drawing [edit]

The principle of solid drawing means taking into account forms in three-dimensional space, or giving them volume and weight.[12] The animator needs to be a skilled creative person and has to understand the nuts of three-dimensional shapes, beefcake, weight, remainder, lite and shadow, etc.[32] For the classical animator, this involved taking art classes and doing sketches from life.[33] One thing in detail that Johnston and Thomas warned against was creating "twins": characters whose left and right sides mirrored each other, and looked lifeless.[34]

In computer animation [edit]

Mod-day estimator animators draw less because of the facilities computers give them,[35] yet their piece of work benefits greatly from a bones understanding of animation principles, and their additions to bones figurer animation.[33]

Appeal [edit]

Appeal in a cartoon character corresponds to what would be called charisma in an actor.[36] A character who is appealing is not necessarily sympathetic; villains or monsters can also be appealing, the important thing is that the viewer feels the graphic symbol is real and interesting.[36] There are several tricks for making a grapheme connect improve with the audition; for likable characters, a symmetrical or particularly baby-like face tends to be effective.[37] A complicated or hard to read confront will lack appeal or 'captivation' in the composition of the pose or character design.

Notes [edit]

a. ^ The twelve principles have been paraphrased and shortened by Nataha Lightfoot for Animation Toolworks.[12] Johnston and Thomas themselves constitute this version good enough to put it up on their ain website.[38]

References [edit]

- ^ Thomas, Frank; Ollie Johnston (1997) [1981]. The Illusion of Life: Disney Blitheness. Hyperion. pp. 47–69. ISBN978-0-7868-6070-viii.

- ^ Allan, Robin. "Walt Disney'southward Nine Old Men & The Art Of Animation". Blitheness Earth Network. Archived from the original on November two, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "List of Best Animation Books". Blitheness Earth Network. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved Oct 21, 2011.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 47.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 47–51.

- ^ De Stefano, Ralph A. "Squash and stretch". Electronic Visualization Laboratory, Academy of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ Willian (July 5, 2006). "Squash and Stretch". Blender. Archived from the original on February sixteen, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 49.

- ^ De Stefano, Ralph A. "Anticipation". Electronic Visualization Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 51–two.

- ^ a b Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lightfoot, Nataha. "12 Principles". Animation Toolworks. Archived from the original on June nine, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 53, 56.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 56.

- ^ Willian (July 5, 2006). "Staging". Blender. Archived from the original on February sixteen, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 56–8.

- ^ a b Willian (July 5, 2006). "Straight Alee Action and Pose to Pose". Blender. Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ De Stefano, Ralph A. "Straight Alee Action and Pose-To-Pose Activeness". Electronic Visualization Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 59–62.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. sixty.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 61–2.

- ^ Willian (July 5, 2006). "Slow In and Out". Blender. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 62–3.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 63–4.

- ^ De Stefano, Ralph A. "Secondary Action". Electronic Visualization Laboratory, Academy of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 64.

- ^ De Stefano, Ralph A. "Timing". Electronic Visualization Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 64–5.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 65-6.

- ^ Willian (June 29, 2006). "Exaggeration". Blender. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ De Stefano, Ralph A. "Exaggeration". Electronic Visualization Laboratory, Academy of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), pp. 66–7.

- ^ a b Willian (July v, 2006). "Solid Drawing". Blender. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 67.

- ^ Lasseter, John (Baronial 1987). "Principles of traditional animation practical to 3d reckoner blitheness". SIGGRAPH Calculator Graphics. 21 (4): 35–44. doi:10.1145/37402.37407.

- ^ a b Johnston & Thomas (1981), p. 68.

- ^ Willian (June 29, 2006). "Entreatment". Blender. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Thomas, Frank; Ollie Johnston (2002). "Animation Tips: Principles of Physical Animation". Frank and Ollie. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

Farther reading [edit]

- Bancroft, Tom; Glen Keane (2006). Creating Characters with Personality: For Film, Goggle box, Animation, Video Games, and Graphic Novels. Watson-Guptill. ISBN978-0-8230-2349-3.

- Kilmer, David (September 28, 1999). "Disney'south ILLUSION OF LIFE tops best animation books poll". Blitheness World Network. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Lasseter, John (July 1987). "Principles of Traditional Animation applied to 3D Figurer Animation". ACM Estimator Graphics. 21 (four): 35–44. doi:x.1145/37402.37407.

- Mattesi, Mike (2002). Force: Dynamic Life Drawing for Animators, Second Edition. Focal Press. ISBN978-0-240-80845-i.

- Osipa, Jason (2005). Finish Staring: Facial Modeling and Blitheness Done Right (second ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-0-471-78920-8.

- Whitaker, Harold; John Halas (2002). Timing for Animation. Focal Press. ISBN978-0-240-51714-8.

- White, Tony (1998). The Animator's Workbook: Pace-By-Pace Techniques of Drawn Animation . Watson-Guptill. ISBN978-0-8230-0229-0.

External links [edit]

- The illusion of life, a elementary animated illustration of the twelve principles.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve_basic_principles_of_animation

Posted by: kernsurvis.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Animation Skills Include All Of The Following, Except Which?"

Post a Comment